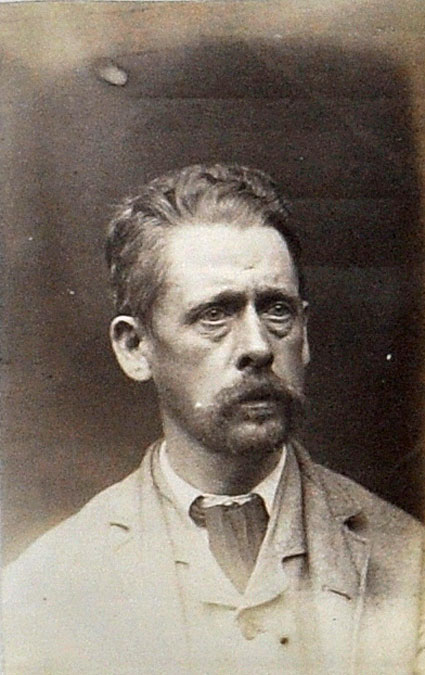

Robert Mackenzie at the time of his admission to gaol in 1883 (David Shield)

This article first appeared in OHTA News, vol. 36, no. 3 (July 2012). An earlier photograph of the 1875 Mackenzie organ now at St George's Anglican Church, Flemington (Travancore) has been replaced here by a more recent one showing the restored casework, and reference has been made in footnote 28 to a subsequent article by David Shield concerning the relocation of the Bishop organ at St David's Cathedral, Hobart, in 1873-74.

Robert Mackenzie arrived in Melbourne with his wife and two young daughters in November 1871. He had accompanied the Melbourne Town Hall organ built by Hill & Son from London and was to supervise its erection. His early career is sketchy and can only be extrapolated from minimal information. He chose to stay in Australia and his early career looked promising. For whatever reason, flaws of character, poor work practice, an unfavourable working environment, his career was not to flourish. His move to South Australia was not successful. Competition from George Fincham in Melbourne followed him. Financial difficulties led to dubious work practices and he was to serve a term at Her Majesty's pleasure. A major health concern may have contributed to his difficulties. He seemingly died a broken and lonely man. To promote his business in Victoria, Mackenzie prepared a brochure for the clergy and general public in which he made certain claims.1 Although much is conjectural about his training and early experience some tentative conclusions may be drawn.

Robert Mackenzie at the time of his admission to gaol in 1883 (David Shield)

In the brochure Mackenzie claimed "extensive experience" at the "celebrated organ manufactories of Messrs Hill & Son, Gray and Davison, and Henry Willis". How extensive? Because he claimed to have been chosen to come out by Hill & Son, it may be reasonably assumed it was with them that he had the most recent experience. He also claimed to have had "entire supervision and charge of rebuilding" several organs. He then lists seven London churches plus the addition of the Echo organ to Leeds Town Hall.12 All were organs of Gray & Davison with work undertaken between 1865-1869. This leaves a period at the beginning of his career available for work with Willis.

It is not clear with whom Mackenzie learnt his trade. Unfortunately there is a discrepancy of four years determining his birth date.3 Assuming he was born c.1840 and undertook a seven-year apprenticeship commencing at the age of 11, he could have been a trained journeyman by 1858 at the earliest. On this basis, ignoring his apprenticeship, it can be conjectured that he worked with Willis for five years (1858-1863), Gray & Davison six years (1864-1869) and Hill & Son (1870-1871) for two before emigrating. A tendency to exaggerate suggests Mackenzie's "extensive experience" meant breadth of exposure rather than longevity of employment.

There is a question as to why Mackenzie came to Australia. Matthews writes that:

He had been sent to Melbourne by the famous London firm of Hill & Son to erect their organ in the Melbourne Town Hall.4

Douglas Renton, a tuner previously sent by the firm, also claimed to have been sent with expectations to help erect the organ. Renton had previously supervised the erection of a Hill instrument imported by the firm of Wilkie Webster and Allan, for Christ Church South Yarra.5 Mackenzie claimed to have been "selected" by Hill & Son, saying "it was the Hill wish that I should erect all their instruments sent out".6 While both Fincham and Dodd were known to travel to superintend the construction of their organs this was not the case with overseas builders such as Bishop or Hill. It is more likely that poor working conditions in the organbuilding trade in England7 led Mackenzie to offer to come to Australia, an offer that was accepted. Mackenzie did receive a letter from Hill in 1877 outlining all particulars of the Adelaide Town Hall instrument, but there is no way of knowing whether this was sought by Mackenzie or part of some compact with Hill. Because he brought his whole family, wife and two children, it may be inferred that Mackenzie intended to use the opportunity to emigrate, subsequently twisting the truth to promote his business. Neither man remained an employee of the firm.

The family arrived on the Lammermuir, the same ship transporting the Melbourne Town Hall organ. In association with Renton, Mackenzie set about erecting the instrument. On completion of the task in August 1872 they combined to create a business called Mackenzie and Co.8 How the business was structured, whether a formal partnership or some loose profit sharing arrangement, is unknown. Renton advertised as manager of Wilkie Webster and Co for most of 1872 and Mackenzie was seen to come from them in March 1874. The business operated from 3 Latrobe Street West.9

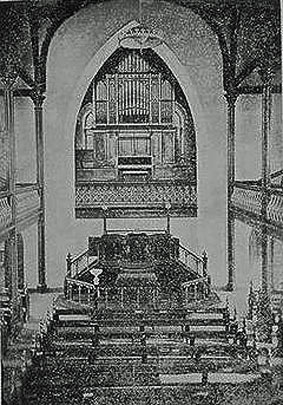

The 1873 Mackenzie organ at the Wesleyan Church,

Golden Square, Bendigo, Vic (State Library of Victoria)

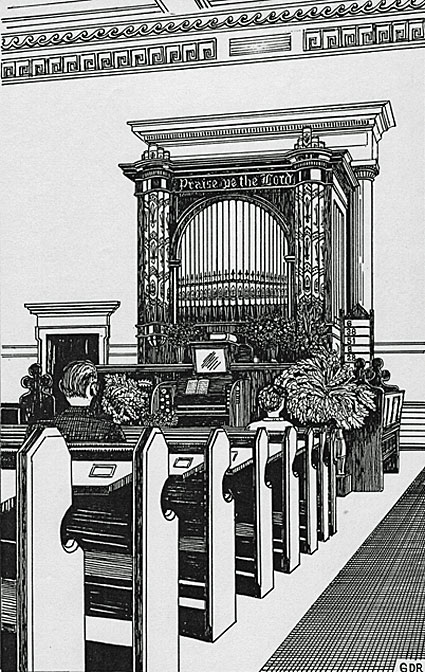

The 1874 Mackenzie organ at the Congregational Church, Collingwood, Vic

(drawing by Graeme Rushworth from an article in Pix magazine)

The 1874 Mackenzie organ in The Scots' Church, Melbourne

(The Scots' Church archive)

For a few years Mackenzie & Co seemed to flourish. Mackenzie was to work in and from Melbourne until 1878. During this time he claimed to have built new organs for eight churches in Victoria and, from his brochure, was building the organ at St Patrick's Cathedral. He also erected organs in Tasmania, South Australia, and Western Australia.

The care of the Melbourne Town Hall organ had been entrusted to Mackenzie and he kept the office until rumblings in April 1875. It was reported to the mayor that the organ was "out of repair" though a report by Plaisted pointed to problems related more to tuning. Subsequently there was a move to dispense with his services as tuner.10 It is likely that by then Renton had returned to Scotland. In May, Mackenzie travelled to Perth to erect the organ at Wesley Methodist Church and shortly after his return the Town Hall Committee advised the Council "that Messrs Lee and Kaye be engaged to take care of, repair, and tune the Town hall organ in place of Mr Mackenzie." Three months later the same Committee recommended that at the request of Lee and Kaye the task be entrusted to Mr John Fincham (sic).11 The contract passed from Mackenzie who returned to Perth in November to erect the St George's Cathedral organ.

The 1874 Mackenzie organ at the German Lutheran Church,

East Melbourne, Vic (John Maidment)

The 1875 Mackenzie organ for Christ Church Anglican Church, Castlemaine, Vic,

now at the St George's Anglican Church,

Flemington (Travancre), Vic (John Maidment)

Competition with Fincham was inevitable. Early in 1876, Mackenzie secured the contract to supply a large organ for St Patrick's Cathedral, undercutting Fincham's quote. Some work was complete by March and the pipework, ordered from London, was to arrive the following year.12 In March 1877, Mackenzie secured the contract to erect the organ for the Adelaide Town Hall. The parochial preference had been for local Johann Wilhelm Wolff but he did not lodge a tender. Anticipated to take a month, the task took five times longer owing to poor planning and coordination on Council's behalf. Mackenzie was able to return to Melbourne for five weeks and take delivery of the pipes for St Patrick's.13 After returning and completing the erection of the Hill organ, the Bishop organ at St Peters Cathedral was to be erected "by the skilful as well as energetic, labour of Mr. Mackenzie".14

Whether Mackenzie over-stretched himself or underestimated his financial commitments is not clear. The St Patrick's contact seemed lucrative enough. He advertised for an apprentice and a boy to help with the work and paid for advertising in the Fitzroy Mercury to Christmas 1876.15 However, he did ask for an advance of £10 against the Adelaide contract as he had "to wait three months for any of the funds that I have expended in organs in Melbourne."16 By August 1879 St Patrick's was still not finished and it was left to Fincham to hand over the complete organ in April 1880.17

Mackenzie may have been encouraged by the business opportunities in South Australia. Shipping records do not seem to indicate when Mackenzie and/or his family moved to Adelaide. Wolff was now aged 59 and it is suggested that for the next two years Mackenzie may have worked with him. If this were the case he would have had a hand in the last five instruments made by Wolff before he retired.18 It is probable also that Mackenzie acquired the tuning round as it is on record that he tuned many of Wolff's organs.

An organbuilder generally cannot work entirely alone. He must either employ someone or be employed by someone else. Employed by firms in London, Mackenzie was surrounded by colleagues. Once in Melbourne he was on his own. He teamed up with Renton and was then supported by Lee & Kaye. In 1876 he sought a boy and apprentice to help him. In Adelaide it is suggested he may have worked with Wolff. After Wolff's retirement he would have been on his own again.

Although Mackenzie was very critical of Broad, there is a suggestion that he actually worked for Broad during 1885. Referring to a new organ on view at Broad & Co in Hanson Street, the newspaper said:

Much of the work has been carried out by the foreman, whose experience gained in the establishment of Hill and Son, makers of the Town Hall organs, Adelaide and Melbourne, is some guarantee of His skill.19

By this description it is concluded that Mackenzie was the unnamed man. This being the case, the current organs at Moonta, Moonta Mines and perhaps Kapunda show his workmanship.

In 1886 Arthur Hobday reporting to Fincham in Melbourne wrote:

Since writing you I have taken on temporarily an extra hand @ 8/6 per day for case work and the heavy parts he has worked for Mckenzie who bye the bye is serving 12 months in gaol for forgery of Boult's name to a cheque – this man is very smart in fact he gets through more work than Harry and his work is good.20

The following year the offer of Mackenzie and Edward Warhurst was accepted to move and repair the organ at St Michael's Church, Mitcham. It would seem that Warhurst was a close friend of Mackenzie's. A carpenter and piano tuner, the connection is interesting and might benefit from further research. It is clear he helped Mackenzie in 1887. Perhaps he was the man taken on by Hobday? It is perhaps coincidence that Mackenzie gave his address as Sturt Street on his arraignment in 1881, the same street in which Warhurst lived.21

Mackenzie had many addresses. The factory was at 3 Latrobe Street until July 1874. A second business address is given with Lee and Kaye at 17 Collins Street Melbourne. In 1876 Mackenzie advertises for an apprentice giving an address at Balmain Street Richmond and finally 40 George Street Fitzroy. The latter heads his publicity brochure but is scratched through by February 1877 when Mackenzie asks a reply to be sent care of the Melbourne Town Clerk. It is assumed the Balmain Street Richmond may be his residence over this period but needs further research. Exactly when in 1878 the family moved to Adelaide is not clear. Residency shifted. Mackenzie rented two cottages in Jeffcott Street North Adelaide from Joseph Ashton, solicitor, at a weekly rental of £1. By 1881 he had become irregular in payment and was £33.14.0 in arrears. The front room of one property was used as a workshop, the back two rooms being sub-let. The family presumably lived in the other cottage. By 1884 Mrs Mackenzie speaks of her neighbour Mrs Shadgett of Mill Street North Adelaide. In April 1886 Mackenzie was to give his address as Sturt Street Adelaide, and in 1905 his final address is given as Rundle Street Adelaide.

It would seem that 1881 was a pivotal year in Mackenzie's life possibly adding to a feeling of insecurity. Fincham & Hobday were to provide professional competition beginning business in September, and immediately seeking the tuning and maintenance of the Town Hall organ. Wolff had been given the first contract in 1878 and was followed by Robert Daws. In May 1879 Mackenzie's tender for repair and tuning was accepted through to August 1881 when it passed to J.J. Broad.22 The fact that Hobday was not successful in his tender emphasises perhaps the parochial nature of the Town Council. Nevertheless, Mackenzie clearly felt threatened by Fincham & Hobday and this was not unfounded. Hobday wrote to Fincham saying

McKenzie is complaining that we tried to ruin him in Melbourne and now again in Adelaide so I am told by one of the Baptist deacons.

He then added the acerbic comment "Don't you feel for him?"23

In terms of building and erecting instruments in his own right in South Australia, only one instrument is known. The organ was the third at All Saints Church of England, Hindmarsh and replacing an instrument by Wolff of 1870. Apparently after a successful opening in October 1881 it was immediately found to be "altogether unfit for use" and was rebuilt by Fincham & Hobday.24

The 1882 Mackenzie organ at All Saints' Anglican Church, Hindmarsh, SA (David Shield)

Financial pressures led Mackenzie to dubious work practices. A strategy to gain income, employed by both Broad and Rendall, was to create a fire and claim on insurance.25 This Mackenzie did on the morning of Friday 25 March 1881. Although the jury of the coroner's enquiry found he had lit the fire and was committed for trial, the judge of the Supreme Court dismissed the case. Two years later things were no better and he attempted to pass a cheque in the name of Arthur Boult, the organist at St Peter's Cathedral. He was not so lucky this time, was caught, and sentenced to imprisonment for one year with hard labour served at Yatala prison. Convicted on 6 April 1883 he was discharged on 11 December that same year.

From his prison record we have a physical description of Mackenzie. In imperial measure, Mackenzie was not tall, 5'6 ¾" in height, with slight build, weighing 9 stone 10 pounds. His complexion was given as "dark". His hair was grey. He had blue eyes, wore a moustache, and his teeth were imperfect. He had at least a basic level of education. It was noted he could read and write. His handwriting style, while large and somewhat untidy, was clearly legible. He was quite prepared to defend his reputation in letters to the daily press and did so on at least two occasions.26

Of the rest of the family there is little information. His death certificate indicates his wife, Martha Ann, predeceased him though there is no public indication of her passing, nor does there appear to be any burial record. At the time of the fire in 1881 Mrs Mackenzie was "sleeping at the bay" viz. Glenelg. In April 1884 she was also supposed to have been visiting Glenelg but missed the train and went to the Seven Stars Hotel in Angas Street instead. Here she was sexually assaulted. The case was sensationalised, detailed reports being given in both daily papers. The prosecution inferred Martha was addicted to liquor, which she of course denied. The case was eventually dismissed on the grounds that the behaviour was regarded as consensual.27 Of his daughters, the elder now aged 15, was with him in North Adelaide on the morning of the fire and gave evidence at that inquest. Virtually nothing else is known.

In all of this there is a sleeper. Mackenzie died in 1905 from diabetes. The onset of the disease is not known. Added to his meagre financial situation and the stresses of his daily life the disease may well have led to depression. There are vague, unsubstantiated hints of an increasingly dysfunctional if not separated family unit. All this in turn may have been salved through alcohol. While suppositional, diabetes may well have been a factor in much of Mackenzie's later career.

This brief overview has made no attempt to analyse Mackenzie's work. While it has attempted to tabulate his work, an understanding of his ideas as to tonal structure or the quality of his workmanship has not been questioned. It is clear that a more detailed study of his potential might find a man who should be less maligned and better understood; a man with reasonable skill, subjected to harsh competition, but hampered by a meagre financial income. On the other hand it may find a loner lacking in business acumen, subject to human frailty, and affected by a ravishing disease.

Robert Mackenzie's star rose and then fell. He had trained as an organbuilder and had experience with Willis, Gray & Davison, and Hill & Son, in London. He emigrated to Australia in 1871 and erected the Melbourne Town Hall instrument. He embarked in business and for some years showed promise, constructing and erecting pipe organs in Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania and Western Australia. In 1877 he was invited to erect the Hill instrument for the Adelaide Town Hall and moved here to this city. He was not to be successful. Financial difficulties led to dubious business practices and competition from Fincham & Hobday led to a meagre existence. Little is known about his family life. He died in hospital suffering diabetes and was buried in common ground, seemingly a broken and lonely man.

A checklist of work known or surmised to have been undertaken by Robert Mackenzie follows:

1863/1868 |

St Giles, Cripplegate |

Gray & Davison, repairs / improvements 1851, 1863 |

1864-1868 |

St Mary's, Woolnorth [Woolnoth] |

Gray & Davison, tuning from 1864, rebuild 1868 |

1865 |

Town Hall Leeds: Grand Organ |

Gray & Davison, echo organ added 1865 |

1866/7 |

St James Garlick Hill [Garlickhythe] |

Rebuild |

1856-1866 |

St Michael's [Paternoster Royal] College Hill |

Gray & Davison, repair 1856; relocated 1866 |

1868 |

St Dionis Backchurch Church |

Gray & Davison, rebuild |

|

St James' Church, Camden Town |

|

? |

St Phil[l]ip's Church, Bethnal Green |

Needs verification |

1872 |

Melbourne Town Hall |

Erection Hill & Son organ |

1873 April |

Wesleyan Church, Golden Square, Sandhurst [Bendigo] |

New organ (rebuilt and altered) |

1873 May |

Wesley Church, Lonsdale Street, Melbourne, Vic |

rebuilt Nicholson organ Argus Fri 30/5/1873 p. 5 |

1873 October |

Wesleyan Church, Kent Town, Adelaide, SA |

Erection Hill & Son organ |

1873 Nov |

St Andrews Presbyterian Church, Ballarat, Vic |

New organ (greatly altered parts survive at Holy Trinity Church, Kew, Vic) |

1873 Dec |

St Francis' Catholic Church, Melbourne, Vic |

Additions to Bevington organ |

1874 |

St David's Cathedral, Hobart, Tas |

Relocation Bishop organ to new building.28 |

1875 May |

Unitarian Church, Grey Street, Eastern Hill, Vic |

New organ (possibly the organ now at St Monica's Catholic Church, Footscray) |

1874 July |

Congregational Church Oxford Street Collingwood, Vic |

New organ (broken up 1950s) |

1874 Nov |

The Scots' Church, Collins St, Melbourne, Vic |

New organ (parts currently in storage after two rebuildings) |

1875 May |

Wesleyan Church, Perth, WA |

Erection Bishop & Son organ |

1875 May |

Lutheran Church Eastern Hill, Melbourne, Vic |

New organ Lee & Kaye (Mackenzie) (extant, rebuilt twice) |

1875 August |

Christ Church, Castlemaine, Vic |

New organ (probably at St George's Church, Flemington, Vic) |

c.1875 |

Christ Church, Ararat |

New organ (destroyed) |

1875 Nov |

St George's Cathedral Perth, WA |

Erection Hill & Son organ |

c.1876 |

St Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne, Vic |

New organ, incomplete construction (completed by George Fincham) |

1877 |

Adelaide Town Hall, SA |

Erection Hill & Son organ |

1877 |

St Peter's Cathedral, Adelaide, SA |

Erection Bishop & Son organ |

1878 |

St Michael's Church, Mitcham, SA |

Erection Bishop & Son organ |

1878 June |

Bentham Street Chapel, Adelaide, SA |

New organ, Wolff (Mackenzie) |

1879 Jan |

St Luke's Church, Whitmore Square, Adelaide: second organ |

New organ, Wolff (Mackenzie) (destroyed by fire) |

1879 May |

St Paul's Church, Pulteney Street, Adelaide, SA |

New organ, Wolff (Mackenzie) (rebuilt twice) |

1879 Nov |

Wesleyan Church, Port Adelaide, SA |

New organ, Wolff (Mackenzie) (at St Aloysius' Catholic Church, Caulfield, Vic) |

1880 Dec |

Wesleyan Church, Norwood, SA |

New organ, Wolff (Mackenzie) |

1880 |

Christ Church, Kapunda, SA |

Organ rebuild, Broad (Mackenzie ?) |

1881 |

All Saints' Church, Hindmarsh, SA |

New organ (broken up) |

1882 |

W. Rendall organ, SA |

Supplied bellows |

1885 |

YMCA Adelaide / All Saints' Church, Moonta |

New organ, Broad (Mackenzie ?) |

1887 |

St Michael's Church, Mitcham, SA |

Repairs / Relocation Bishop & Son organ |

1888 |

Wesleyan Church, Moonta Mines, SA |

New organ, Broad (Mackenzie ?) |

1893 |

Brompton Wesleyan Church, Brompton, SA |

Additional 3 ranks |

1897 |

St Luke's Church, Whitmore Square, Adelaide, SA |

Renovated Wolff organ |

No work in London is claimed for Willis or Hill & Son.

In South Australia the following organs were known to be tuned by Mackenzie. Complete tenure requires further research. Alberton Methodist (1879), Norwood Baptist, (1881) North Adelaide Baptist (1881), Unitarian (1881) and Town Hall Adelaide (1879-1881).

1 An copy of this leaflet was used as notepaper in support of his specification to erect the Adelaide Town Hall organ in 1877 (Adelaide Town Clerk Letters in no. 453 / 1877, dated 26/2/1877).

2 The listed churches were: St Giles Cripplegate, St Mary's Woolnorth, St Dionis' Backchurch, St James' Garlick Hill, St Michael's College Hill, St James' Camden Town, St Phillip's Bethnal Green, all of London, "He also added Echo Organ to the grand Organ in the Town hall, Leeds." With the exceptions of St James' Camden Town and St Phillip's Bethnal Green, the London instruments are mentioned in N.M. Plumley, The Organs of the City of London (1996). Leeds Echo organ of 1865 is mentioned in N. Thistlethwaite, The Making of the Victorian Organ (1993), p. 284.

3 Mackenzie's date of birth is uncertain. In 1881 he claimed to have had 30 years experience as an organbuilder which gives a starting date of 1851. Assuming he began an apprenticeship at the age of 11 this would also give a birth date of 1840. His hospital record at time of death in 1905 gives his age as 65 confirming a date of birth 1840. His prison record of 1886 states his age as 49 i.e .born 1837. The 1871 census gives his age as 30, suggesting he was born in 1841 [BIOS website information].

4 E.N. Matthews, Colonial Organs and Organbuilders, p. 26. This is supported by a letter from F.J. Sargood informing the Melbourne council the organ had been shipped and that "Messrs. Hill and Son, the makers of the organ, had sent out a competent builder, who, with a man from Messrs. Hill's already in Melbourne, would, he hoped, proceed at once with the erection of the organ when it arrived." The Argus 31/10/1871 2s.

5 The Argus 11/7/1871 p. 5; Matthews, op cit, p. 153. Renton also built a one manual organ for the Williamstown Presbyterian Church (Williamstown Chronicle 24/1/1874 p. 5).

6 Adelaide Town Hall specification, op cit.

7 L. Elvin, Bishop and Son, Organ Builders, p. 70.

8 The Argus 22/8/1872 p. 3.

9 The Argus 13/9/1872 p. 4.

10 The Argus 13/4/1875 p. 5; Argus 10/5/1875 p. 5.

11 The Argus 23/8/1875 p. 5; Argus 25/8/1875 p. 6.

12 Ref: Matthews, op cit, p. 28.

13 see D. Shield, 'Erecting the Hill with Robert Mackenzie', OHTA News (October 2009), pp. 15-19.

14 Register 3/9/1877 p. 7.

15 The Argus 25/2/1876 p. 1; The Argus 6/4/1876 p. 1. It is doubtful, but unknown, whether Mackenzie was successful in getting this assistance. Mercury (Fitzroy) 15/7/1876 p. 4. The advertisement was regularly repeated to 23 December 1876.

16 Ref: ATH letter.

17 Argus 9/8/1879 p. 12; Argus 22/4/1880 p. 5.

18 Bentham St Chapel Adelaide (June 1878); St Luke's Whitmore Square second organ (January 1879); St Paul's Pulteney St (May 1879); Port Adelaide Wesleyan (November 1879); and Wesleyan Norwood (December 1880). Family folklore has it that Wolff met Dodd on his arrival in Adelaide, stated he was retiring, and offered him the business. This would be an error as Hobday was the senior partner at the time, but could well have been Mackenzie whom Wolff would have known from the erection of the Adelaide Town Hall organ. Conversation between John Wolff (grandson) and author 5/1/1984.

19 Register 7/11/1885 p. 5.

20 Fincham & Hobday Letters transcribed by Ronald G Newton, Letter no. 12/134, dated 8 May 1886 Hobday to Fincham. This person might have been E. Warhurst, organist at Hindmarsh and later at St Luke's, Whitmore Square.

21 Edward Warhurst played on three Wolff organs. The first was at All Saints Hindmarsh at the time the Mackenzie instrument was acquired. He moved to St Paul's Pulteney Street and then St Luke's Whitmore Square where Mackenzie overhauled the organ in 1897. His son was organist at Mitcham when Mackenzie was asked to move the organ in 1887.

22 Register 16/2/1882 p. 6 (letter to editor).

23 Fincham & Hobday Letters, op cit: Letter no. 12/35, dated 22 Nov 1881 Hobday to Fincham.

24 Register 31/10/1881 p. 5; Register 25/1/1882 p. 5; Fincham & Hobday letters, op cit. Letter no. 12/39, dated 24/12/1881 Hobday to Fincham.

25 Broad with Rendall Register Fri. 31/10/1879 p. 6; and Rendall alone Register Sat. 14/4/1883 p. 5.

26 Register 22/11/1881 p. 6; Register 16/2/1882 p. 6.

27 Coverage in both Advertiser and Register appeared on 15, 16, 17 April and 5, 14 June. The reports vary quite markedly, the Advertiser being perhaps more sympathetic to Mrs Mackenzie.

28 David Shield, 'Barchester on the Derwent,' Organ Australia (Autumn 2015), pp. 32-35.